All I Really Need to Know (About Leadership), I Learned in Mexico

Before we heard from Stephen Covey about the seven habits needed to become “highly effective people” or from Jim Collins about the five steps that would take us from “good to great,” author Robert Fulghum taught us a simpler lesson: all we need to know about living a good life can be learned in one contained classroom — kindergarten.

In his 1986 best-seller, “All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten,” Fulghum shared his view that the basic rules most of us were taught in kindergarten were foundational to a happy, healthy, and productive life — rules such as “share everything,” “play fair,” “don’t hit people,” and “clean up your own mess.”

I say “most of us” because I’m one of the increasingly rare breed of people who didn’t attend kindergarten, which left me behind the curve in some of those important life lessons (especially the one about taking a nap every afternoon, which would have done wonders for my surly disposition in my early teens).

While I might have missed out on the lessons the rest of you learned in kindergarten, I had a later experience in a different sort of classroom that taught me everything — or, at least, almost everything — I needed to know about leadership. In homage to Fulghum’s work, I’d like to share some of those lessons with you.

Building with Amor

My classroom experience was made possible by Amor Ministries, a faith-based organization founded in San Diego for the purpose of ministering to the poor across the border. Amor’s mission statement consists of three simple words, “Come. Build. Hope,” which is about as pure and powerful a mission statement as you’ll ever read.

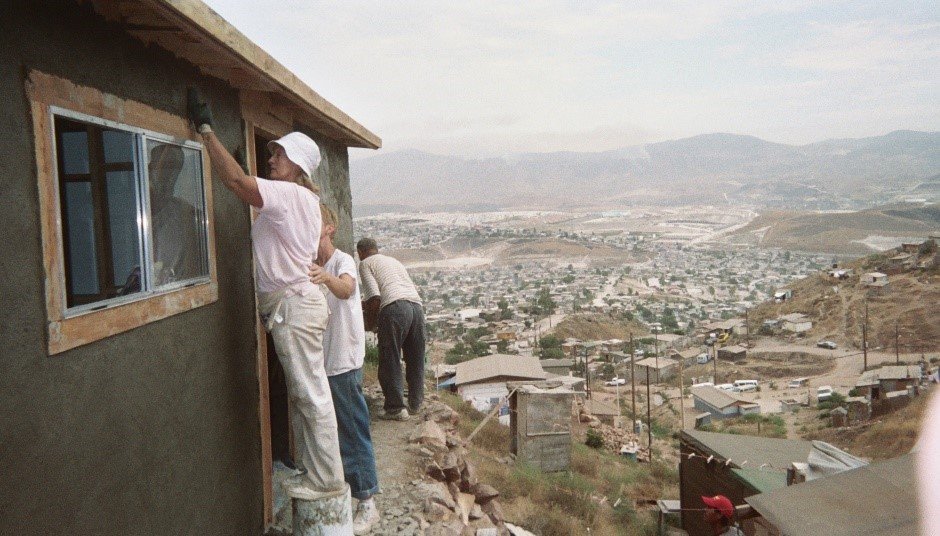

Amor lives out its mission statement by coordinating groups of volunteers that build modest homes in the Baja California and Puerto Peñasco regions of Mexico. The homes are simple structures built on concrete slabs, with stucco walls, a slanted roof, one door, and one window. For safety reasons, power tools are not allowed on the building sites, so the construction has to be performed by hand using manual saws and hammers to assemble the wooden frame and hoes and shovels to mix the concrete and stucco.

I first learned about Amor in the summer of 2001 when my church took over 300 people on a mission to build homes in the Tijuana area. We slept in tents brought with us from Indiana in a make-shift tent city set up in a quarry on the side of a mountain. Between the rocks under our sleeping bags, the snoring from our fellow missionaries, and the demon roosters that awakened us at first light, we didn’t get much rest, and working in the hot Tijuana sun all day was every bit as exhausting as you might suspect — especially for those of us who were desk jockeys back home, unaccustomed to hard manual labor.

It was the hardest I’d ever worked, the worst I’d ever slept, the dirtiest I’d ever been, and I loved every minute of it. (Well, except for the demon roosters and the bucket showers at the end of each day, which were the only cold things we experienced all week.)

My oldest daughter Sam (then eight-years-old) joined me on this first trip, creating daddy-daughter memories that will last a lifetime. After hearing our stories upon our return, the rest of our family decided to join us on future trips. Collectively, we went on a total of seven mission trips with Amor over the next decade, helping build over 30 homes for grateful families and creating a storehouse of memories for ourselves.

Leadership Lessons Learned

Anyone who knows me can tell you my handyman skills are about as non-existent as the mullet I used to rock in the 80’s, but I was able to use a shovel, carry things, and mix cement to the appropriate consistency with a garden hoe. As much as I enjoyed the physical labor associated with building these homes, however, I wanted to contribute at a deeper level, so I eventually volunteered to lead a number of these mission trips.

Like Fulghum’s kindergarten experience, the opportunity to lead these mission trips provided a master class in leadership lessons I couldn’t have replicated at any Ivy League school or corporate training room. Here are five of the most powerful lessons I learned, which I’d like to share with you.

Lesson 1: Start with The Why

The first lesson I learned from leading these trips was later captured by Simon Sinek in his book by the same name: “Start with The Why.” Before deciding what to do or how to do it, your team first needs to understand the why behind a situation. Effective leaders must cast a vision for their team that both explains (why are we doing this?) and inspires (why does it matter?).

Casting a vision might seem superfluous when you’re doing something as tangible as building a home for impoverished families, but our trips were about much more than the physical act of construction. We were attempting to build relationships with the families, strengthen our bonds with each other, and deepen our connection to the Creator who made all these things possible — all things that required a “why” to accomplish.

One year, for example, our vision for the trip was “Being the Body,” which was taken from the imagery used by the Apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 12:27 to describe how the early Christian church was made up of people with different gifts, weaknesses, and strengths, much like the different parts of the human body.

We used this vision to explore how each member of our team — from the cooks to the drivers to the construction crews —could contribute in a unique way to our mission, and also how we could learn from the families we were technically there to serve by the way they lived their lives. “Being the Body” provided the context for why we were traveling across the continent to bless and be blessed by people we were unlikely to see again.

Leaders, what is the “why” motivating your team?

Lesson 2: Plan the Work, Then Work the Plan

One of the early self-help gurus, Napoleon Hill, is credited with saying “plan your work and work your plan.” The wisdom of this saying became apparent to me over and over again during the trips I led to Mexico, which required months of advance planning and recruitment, arranging for transportation of our volunteers and supplies to San Diego and then across the border to the Tijuana area, the assembly of our temporary camp site in the desert, the construction of the homes themselves, and finally, the return travel home.

What I discovered as a result of these experiences was that chaos is not an effective leadership strategy. Preparation and organization at the top make room for inspiration everywhere else, and contributors at all levels perform their best when they know their leaders have a plan. Anxiety and uncertainty are replaced by confidence, and team members are freed up to be fully present and focus on their role in achieving the “why” when they know their leaders are prepared. After all, even a circus is carefully planned and choreographed in advance!

Leaders, do you invest as much time in planning the work as you do executing it?

Lesson 3: Flexico, Mexico

Great thinkers like from Prussian military strategist Helmuth von Moltke (“no plan survives contact with the enemy”) and boxer Mike Tyson (“everyone has a plan ‘til they get punched in the mouth”) have taught us that planning can only get you so far, however.

No matter how carefully you plan as a leader, unanticipated events will occur that require you to make adjustments on the fly, often with your team members watching for cues as to how they should react. In times of crisis, teams tend to take on the mindset of their leader, and leaders who are unfazed by adversity will create teams that respond equally well under pressure.

Our trips to Mexico taught me to recognize not only that disruption is inevitable, but also that effective leaders build it into the planning process. Our team developed the saying “Flexico, Mexico,” as a mantra we would recite whenever the unexpected occurred, which happened with surprising regularity. This phrase helped us accept the reality that unscripted moments were unavoidable and, in some cases, actually made the experience more meaningful.

One of these unscripted moments occurred late one evening when another church group arrived to the campsite well after dark due to car troubles, and our team swung into action by helping them unpack their gear, assisting them in assembling their tents, and firing up our cooking equipment to make them a late-night dinner after a long day of travel. Because our team had arrived early in the day and had purchased extra supplies to create margin, we were prepared for the possibility that something would go wrong and were able to lend support to these other stressed-out volunteers, blessing them in their time of need and enriching our own experience.

Leaders, what steps can you take to model and build a mindset of flexibility into your team?

Lesson 4: Build Around Talent

Coach Mike Krzyzewski (or “Coach K” to my fellow Blue Devils fans) is the winningest men’s college basketball coach of all time and is known for his ability to recruit, develop, and lead talented players into becoming the best version of themselves. Perhaps his greatest strength, however, is his willingness to change up his system each season to take into account and maximize the talents of the players on that particular team, unlike other coaches who insist the players fit into their rigid schemes.

I first began to understand the brilliance of Coach K’s philosophy while planning trips to Mexico. I learned that while some members of our team were gifted in the necessary skills of construction and mechanical problem-solving, others had very different but equally indispensable gifts:

Dawn, for example, had a mind for logistics, an unerring sense of direction, and experience as an EMT. So, rather than assigning her to a construction crew, I put her in charge of buying supplies, first aid, and guiding our caravan across the border and to remote worksites each day. She was a natural!

Beth, who owns an HVAC business back home, had a passion for hospitality and team-building. She used these gifts to organize crews to prepare three meals a day for each of us while we were in Mexico, and then to take our unused supplies and camp chairs back across the border to the homeless population when our homes were finished.

David was a high school shop teacher who loved nothing more than teaching others how to work with their hands, which made him a natural candidate to lead construction crews and train future crew leaders.

Others were gifted in singing, leading stretching exercises, paying attention to our hydration levels, and generally keeping everyone’s spirits up. Each of them played an invaluable role on our trips, regardless of how well they swung a hammer.

I learned from this experience that leaders can help teams become great by recognizing how each member is wired for greatness and empowering them to do more of that.

Leaders, how are you leveraging the individual strengths of your team members to create a stronger team?

Lesson 5: Leaders Are Not Supposed to Be the Stars of the Team

Perhaps the most important lesson I learned about leadership was that leading is not about being the star of the team, but about equipping others to become stars instead. I learned this lesson through two unforgettable interactions that occurred within minutes of each other.

One of our construction crew leaders this particular year was a talented electrician named Andy, who complemented his construction skills with a remarkable ability to get to the point without letting diplomacy get in the way. One day, as I was shuttling between construction sites to make sure everything was on course, Andy stopped me to share an insight he had gained about my leadership style, which he said reminded him of his brother (also a lawyer in Indianapolis). With my curiosity piqued, I asked, “how’s that, Andy?” Andy responded without hesitation, “well, neither one of you does anything. You just walk around and watch everyone else do the work.” Ouch.

Fast forward twenty minutes, when another team member came to me with an opportunity to show exactly what leaders actually do do (pun definitely intended) when she asked me, “Who’s in charge of the baño?” Setting the scene, some of the construction sites we were building on lacked working restrooms, so we brought our own portable “baños” with us, consisting of a bucket, a plastic bag to hold the waste, and a curtain around it for privacy. Not exactly the bathrooms at the Ritz, but they worked well enough under the circumstances — at least, ordinarily.

On this particular occasion, my team member explained that someone either had become overheated from working in the sun or was overcome by the smell of the baño — TRIGGER WARNING for the squeamish here — and had thrown up in the bucket, causing the plastic bag to slip into the contents. She said that the bag needed to be replaced before the contraption could be used again but no one had the stomach for it, so she came to me to find out “who is in charge of the baños.”

Once she described the, er, messy predicament, the solution became clear: as the leader of our group, I was ultimately in charge of the baños. So, I explained to her that I would take care of it and proceeded to grit my teeth, hold my breath, and do what needed to be done. (Thank goodness I had years of experience in college cleaning up befouled bathrooms at the local watering hole where I worked to prepare me for this!)

The irony of these two interactions occurring almost simultaneously was not lost on me, and I began to see them as the perfect way to describe the role of a leader — at least, the type of leader I aspired to be.

While some might expect to see the leader performing the most complicated tasks when building houses, I learned that leading was different than playing the starring role. The job of a leader is to find people with star potential, put them in a position to utilize their talents, and then provide them the resources, support, and encouragement they need, rather than taking up the spotlight himself. While teams do pay attention to the performance of their leaders when those leaders are required to be in the spotlight for one reason or another, team members respond more favorably when the leaders are putting them in position to be stars themselves. What my friend Andy observed as “not doing anything” was actually leadership in action.

The “Baño Incident,” as it came to be known, illustrated an equally important point: leaders must be prepared to do the dirty work — in this case, the dirtiest of work — necessary for the operation, health, and well-being of the team. In this particular situation, that meant holding my breath and doing something I could not ask anyone else to do. In more typical leadership situations, this means delivering the hard truth, taking responsibility for the team’s failures, and being willing to put your team’s needs above your individual preferences. When you approach it from this perspective of servant-leadership, it turns out that leaders are always in charge of the baños.

Leaders, how can you better serve your team members by putting them in a position to star and cleaning up the messes that can get in their way?

¯¯¯

While building homes in Mexico was a very different sort of classroom than what I imagine kindergarten was like for you, those experiences have had a powerful influence on both the way I lead and the way I coach other leaders. If you’d like to work with a coach who can help you learn from your past experiences and how to become a more effective leader, contact me at mike.tooley@upstreamprinciples.com.